Exactly one year ago, I finished my first creative essay in over a decade. I couldn’t post it right away, because I was waiting for it to be reviewed by a local literary magazine. Needless to say, it was not accepted for publication. So, because I am impatient, and sitting on things does me no good at all, I present to you: my piece. Enjoy.

***

ALMA MATER

On the far side of the town of Oberlin, just before the sidewalk ends, there is a modest gravel driveway, sandwiched between a private residence and a private golf course. I could not say for certain who owns the driveway. It leads to both a maintenance shed and a two-car family garage. My feet belong to neither, but they have shuffled up this path, kicking loose stones, on more occasions than I can count.

What lies at the end of the drive is something of a secret. Two sandstone pillars, barely higher than my head, mark the entrance to a quiet, clandestine copse of trees called the Ladies’ Grove. But for its curious gateway, this place would seem indistinguishable from the adjacent woods, where there is a pond and a meadow and a forbidden fire pit for college students to congregate around after skinny-dipping in the summer. The neighboring forest is larger, with a more convenient entrance, parking for cars, and a rack for bikes. It is where the people go. There are few who would venture this far for an ostensibly unremarkable stand of scraggly trees.

In my soft, leather boots, with the top button of my wool coat fastened against the biting chill, I approach the stone gateway with all the solemnity of a pilgrim. Each square pillar is emblazoned with a word in all caps—LADIES on the left, GROVE on the right. I like to think of this place as forgotten and untouched by time, but the letters and their serifs are grooved too deeply to have withstood centuries of weathering. I consider the thought that someone, at some time, loved this place as I do, enough to preserve it from the slow-rising tide of our modern empire. Whizzing electric golf carts and rainbow plastic playsets mark its boundaries, but their bustle and noise do not penetrate the grove. I am grateful for this gift as I cross the threshold and breathe deep.

The air smells like brown leaves and mud, which makes sense, because it is March, and the ground is beginning to thaw. Instantly, I regret my choice of footwear, as my feet sink into the rich humus, and the cold damp penetrates even the tiniest holes in my well-worn boots. Apart from its clearly-marked entrance, the Ladies’ Grove seems to have no designated trails. Thin, young trees cast dark shadows in my direction, and fallen leaves blanket the ground as far as the eye can see, giving this place the illusion of infinity. Undaunted, I am guided by experience. I have walked these woods long enough to know the way.

It is not a great distance from the gateway to the muddy, sloping banks of Plum Creek. As I traipse through the quagmire, a gentle breeze coaxes a strand of hair from my long braid. I tuck it behind my ear. The marcescent leaves of a young beech tree spring into action, rubbing their dried, pale bodies together to produce a whisper like the quiet rustle of fabric. The sound follows the breeze throughout the woods, a long and haunting sigh. The return of the sun has not yet broken the frigid grasp of winter, and I am struck by the liminality of this moment, where seasons mingle and past and present converge.

Like a naturalist in search of migratory birds, I come to this place in search of memory. The Ladies’ Grove was established in the early days of Oberlin, a sheltered zone where young ladies could wander unchaperoned. Centuries ago, when dense woods still marked the boundaries of settlement, Oberlin’s college was the first in the United States to commit to co-education. Dozens of female students flocked to this isolated swamp town for the chance to prove their intellect, but that promise was only partially realized. Propriety demanded strict scrutiny of the fairer sex. There would be no public speaking, no ancient languages, no stepping out after dark, and absolutely no unsupervised roving in fields and forests. In the 21st century, I can wander wherever I choose, but I return to the Ladies’ Grove as surely as a spotted salamander returns to the vernal pool of its birth.

When I pass through the pillars and into the trees, the memories of the earth beneath my feet entwine with my own. I walk in tandem with my fore-sisters. Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown, before they spoke fearlessly for abolition and women’s rights, led their female peers into the trees to practice the forbidden art of debate and hone their oratory skills. Harriet Keeler, a firebrand suffragette who would go on to publish several botanical field guides, likely had her first introduction to the beauty of the natural world in these woods. Adelia Johnston, who refused to lead the Ladies’ Department if she would not be allowed to teach, was first accepted as a professor of Botany. Did she bring her classes here, a place where young women could grow as wild and beautiful as bergamot? What countless others passed through this forest enroute to fulfilling their dreams?

I imagine these women as I walk, and the long centuries collapse. They stepped over layers of decomposing leaves, same as me. The whisper of their heavy skirts swished through the trees. Their laced leather boots slipped over mossy rocks and into the dark mud. The ringing sound of their eager voices, yet untested, echoed the sweet songs of birds. The scent of rosewater, citrus, and sage mingled with our native wildflowers to create a perfume unique to this place and that time. If I close my eyes, I can smell it. We could not be closer if we walked arm in arm. This is the magic of the Ladies’ Grove.

When I felt alone or defeated in college, as I often did, I came to sit in the woods. On my first visit, I walked a wild, meandering route before I found a place to drop my cardboard cushion in the mud. The spot had called to me with its silence, far removed from the open reservoirs with their jolly student revelers. I could hear Plum Creek washing over pebbles in the distance. Little pools of water collected in the motley carpet of leaves and reflected patches of sunlight onto the backs of my crossed legs. I closed my eyes and sighed.

In the beginning, I believed it was the solitude of the space that made it sacred. The trees were stately pillars, the sun-lit canopy a stained glass masterpiece, the animal cries a chorus. I would return when icy drops of water coated pine needles like syrup, and again when the toads began to whir in harmony. I began to know the charm of all the seasons, and I rarely saw a soul. It was another year before I would discover the origin of my wooded temple and learn to call it by its name. That was when time began to unfold beneath my feet, a layered tapestry of stories bound together by the kinetic thread of memory. Then I knew I was never truly alone.

When we think of repositories of memory, our minds often wander to dusty archives, crowded library stacks, and interactive museum exhibits. I think of these trees: beech, maple, and oak. These botanical sentinels of time lead long lives. From their first roots plunging deep into the soil, until their decaying logs become a feast for fungus, trees may witness the birth of villages, the waging of war, and the growth of our children. Layers of time, like layers of earth, are bound up in these roots. After great trees are felled, I often see cross-sections of their large trunks hanging in buildings, little pins stuck into the wood to mark occasions like George Washington’s birthday or the 1969 lunar landing. We frame them in the context of human events and marvel at their longevity, but there is a way to tell the age of a tree that requires no violence towards its existence. You need only measure its girth.

In a healthy forest, each species of tree has a unique growth factor, a number assigned to them by forestry experts. Multiplied by a tree’s diameter at breast height, this species growth factor is the key to unlocking an individual’s age. For my excursion today, I have engaged the dusty and derelict portion of my brain dedicated to storing mathematical equations. Circumference divided by pi equals diameter. Diameter times species growth factor equals age. I mutter these formulas under my breath like a prayer as my eyes scan the woods around me. It registers, briefly, that I may never have been more focused on a visit to the Ladies’ Grove. I am on a mission.

In my pocket rests a long coil of yarn, which I will use to measure the memories of these trees. Not one to cut corners, I used a ruler to cut the string. With the help of a calculator, I painstakingly determined the approximate diameter of a tree that could have lived alongside Lucy Stone. I run my fingers anxiously over the fibers of the yarn as I walk the length of the creek. My eyes dart left and right. Many of the trunks here seem wide enough to predate the retired golfers making their way across the neighboring green, but none strike me as the great elders I seek.

Heaviness grips my heart and defeat twists knots in my gut. There are only so many trees, and so I turn to leave, unfulfilled. Without a purpose to guide them, the energy has drained from my footsteps. I plod back to reality. My eyes are fixed on the ground, and I move past small, spectacular signs of spring with hardly any interest. A mourning cloak butterfly, its dusky, pristine wings fringed with pale yellow, rises out of the leaf litter. Its flight carries it over a patch of delicate snowdrop blossoms before it disappears back into the infinite brown. A robin sings, long and flute-like, from somewhere overhead. This brightness cannot penetrate the cloud of my disappointment. I feel as gray and mildewed as the rotting leaves crushed under my muddy boots.

The same stone pillars that greeted me earlier once more come into view. I have nearly left this place behind, perhaps discarded it forever as a childish fascination, borne of a post-adolescent depression and nothing more. But something deep in my nature halts my feet and urges me to turn around. The loose strand of hair I had tucked behind my ear is once again plucked free by the wind. The woods at my back come alive with sound. My heart begins to race, and I am overcome. Despite my newfound cynicism, I cannot help but look back.

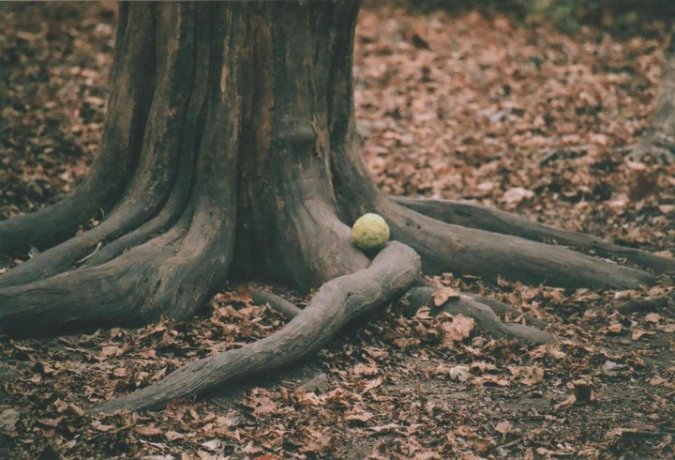

There she stands, as plain as day. The trees cease their whispering as the breeze fades, and I take in the wide, dark expanse of her trunk. My eyes follow the deep furrows in her bark all the way up to her tangled canopy, which towers above the rest. Trees are not as ephemeral as butterflies or birdsong, but this aged white oak has come to my attention just as suddenly.

I am a poor mathematician, yet I do not need the string in my pocket to know this tree is older than the rest and far beyond my expectations. White oaks grow strong and tall, and this tree is easily a double centenarian. As I approach, I notice a basal scar—a smooth, white patch in a field of scaly, gray bark about five feet from the ground. It is shaped like a heart, and something curious about this shape compels me forward. I tip-toe on her thick, mossy roots until I am close enough to touch the exposed wood. I raise my hand, close my eyes, and press my palm onto the smooth surface. Instantly, I feel her presence. The energy that passes into my body is too vague to be electric, and I am too much of a realist to suspect it is spiritual. Yet something stirs within me.

In older forests, there is something biologists call a mother tree, connected to all the others by an acres-wide, underground system of roots and mycorrhizal fungi. The mothers are the giants of the network, sending nutrients through the web to their progeny and their neighbors. When the time comes for a mother to die, the centuries of energy stored in her body will decompose slowly into nutrient-rich soil, a ready-made cradle for the next generation. She is a perpetual caretaker of the community, the method of its endless rebirth.

The woods of the Ladies’ Grove are not as old as they once were, but this white oak mother continues to nurture her kin. Over a century ago, when the first Oberlin women walked these grounds, she might have been a spry teenager, feeding off another mother’s roots. Now she shares this life-force with a new crop of youngsters. Gazing at the current expanse of thin trunks, which had so recently been the cause of my frustration, I am filled with an indescribable sense of warmth, of belonging. I think of the words alma mater, which, when directly translated, describe a mother who nourishes. Like these young trees, I am the descendant of giant mothers—the almae matres of my alma mater—whose decades of work made a fertile bed for my own growth. With each generation of independent, outspoken women, the soil grew richer.

I came to the Ladies’ Grove in search of memory. I wanted to feel the presence of the pioneering women who strolled under these trees before taking on the world. I thought their spirit could only manifest in the heartwood of an aged giant, but memory is not static. It flows. Whether through human history or a vast, symbiotic network of roots and fungus, that memory feeds its descendants, ensuring their survival in a world that is not always open to them. The virgin forest that once surrounded this white oak mother long ago fell victim to the axe; many strong women passed on before their goals were realized; but the young trees of the Ladies’ Grove and I have grown up with the energy of those that came before. In the constant generation of this little grove of trees, as in the continued beating of my heart, their legacy lives on.

As I finally pass through the twin pillars, the ground beneath my feet changes slowly, from soft earth to crushed gravel. I follow the curious driveway, past the garage, past the maintenance shed, until I reach the sidewalk. My legs carry my body back towards town, but I have left a piece of me behind. When I laid my hand on the great white oak, I felt its fragility. Someday it will collapse under the weight of its spring leaves and seed its memories back into the earth—centuries of sunshine and rainfall, of birds’ nests and squirrel quarrels, the sound of rustling leaves, the ringing of passionate voices, and, perhaps, even the light brush of my fingertips.