Love fades away. But things? Things are forever.

– Tom Haverford

I’ll tell it to you straight: I live in a city that can experience all four seasons in a single day. I spent a lot of time in a college town, where my core group of friends rotated based on who was in town for break. I move to a new apartment every nine months, and I’ve never had a boy hold my hand and tell me he loves me.

Change and upheaval have been ubiquitous in my early 20s, but I am stubborn as a mule. I swallowed the stones of constancy a long time ago, hoping they would grind this perpetual uncertainty into something easily digestible. I’d rather drown with my heels dug into the sand than relax my limbs, tilt my head back to the sun, and let the waves wash me ashore. I do not adjust well.

I’m making this post because I’m about to turn 25 years old, and I’ve been feeling a bit swept away. It’s not a bad thing. As a rational adult, I know that change can be good. It can mean a new job, a better home, friends who care, happiness. As a somewhat less rational adult, I’m terrified and convinced it will all go wrong. Everything. Nothing will be good. Anger and sadness. The feline inside takes over, and all I want to do is hiss and claw my way back to the familiar, even if the familiar means being unhappy.

(I may or may not have been a cat in another life. This may also explain my affinity for knocking things off shelves and head massages.)

Now, I’m not really a person who cares about things. Every time I talk to my mom about moving, I tell her I don’t want anything. I don’t want an adult bed with a solid oak headboard that weighs 2,000,000 pounds. I don’t want a couch that can’t be taken apart. I don’t want to put my posters in frames or to own more than one lamp. I want to keep my six-year-old glasses and this pillowcase from the 1970s. I’ll take people’s old clothes, but I won’t buy new ones for myself. I hate things.

But, as I’m about to get older, I’ve been thinking a lot about the things I do own. I may not be able to count on the sun coming out in the morning (thanks, Lake Erie), but most of the things I own are things that keep me feeling rooted. Through every move and every heartbreak–in sickness and in health–these things have been with me. When I hold them, I know certainty. When I hold them, I know strength. When I hold them, I know myself. This is a tribute to those things that, even when I cannot see it, remind me that I can (and will) pull through.

—

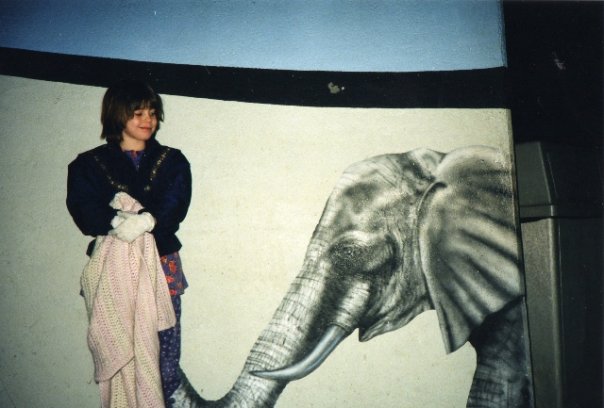

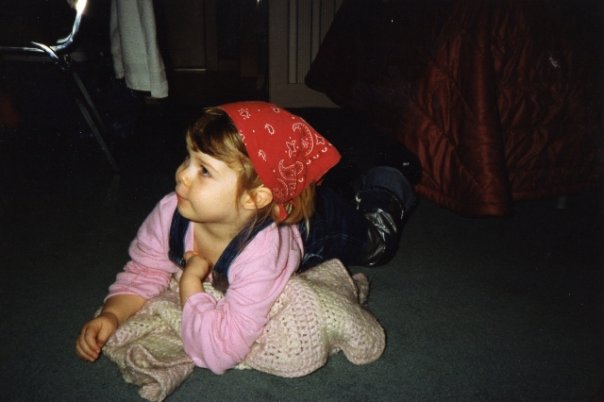

My baby blanket. There is a gray pile of knotted yarn sitting on the bed next to me. Too delicate to be washed regularly, it smells more human than I do with all my shampoo and perfume. It is rough–full of holes and lumps–but every few moments, I pause typing to run the fabric through my fingers. Only I know how this feels. Only I know the inexplicable comfort this action can bring…

I’ve had this blanket since I was born. That’s the excuse I give as I fail to articulate its importance. For reasons unknown to me, I chose it to be mine, and, for reasons unknown to me, I’ve been compelled to keep it. I’ve carried it with me for 25 years, and it has seen the world. I can’t even begin to list the adventures it we’ve shared. Six trips to Europe, a decade of Girl Scout camp, four years of college, spring break trips, bus rides, train rides–even caving! It has sat through every episode of Parks & Rec, every tearful phone call, every all-nighter, every head cold… If I had to describe my soul, it would be this blanket: knotted, faded, worn, but full of love and an unbreakable spirit of adventure.

I’m not an infant or an idiot. This blanket ceased to have a name when I became a teenager. It lost its gender when I graduated high school. When men stay the night, I kick it to the bottom of the bed, and I no longer bring it outside my room. But, until it has completely unraveled to nothing, I will continue to diligently tie its frayed ends together. I will continue running its edges between my fingers. And I will continue loving it as it has loved me.

—

My ring. I have worn this ring on my right hand every day for the past four years. I purchased it only a week before I left Ireland because it was the cheapest one I could find. It didn’t mean much, to be quite honest. I thought it was funny when Irish boys came up with clever excuses to look at my hand to see if I was single or not, but that was about it. It wasn’t until I left the place I’d called home for half a year and set off for a scary adventure all on my own that I found it had any meaning at all.

When I was alone on the train from Berlin to Dresden, feeling lousy, I happened to look down at my hand. In that shiny silver heart, I saw rolling green hills and sheep in the pasture. I saw my friends smiling up at me–Irish, German, American, Portuguese, Austrian. I saw crystal blue harbors and rainbow store fronts. I smelled the grassy rain and heard the music of my soul. I took a deep breath and looked out the window, content.

I lost my ring for four days in Dresden. I anxiously stammered something in German to the hostel owner and then ran upstairs to frantically tear apart my room, looking. My hand felt wrong. I couldn’t even turn the pages in my book. I unpacked my whole bag over and over again until, crying, I called my mom and asked her what I should do. I was distraught. I was sure I’d never be able to use my right hand again.

A few days later, as I arrived at a friend’s house in Frankfurt and loosened the detachable front pouch on my backpack, I found the ring stuck on a string behind the pouch. For four days, that little silver circle had held onto that unreliable piece of string. It had held onto that string through multiple train rides and several panicked searches. It was a close call, but I hadn’t lost it. I breathed a sigh of relief and slipped it back onto my finger. Ireland–and all I loved about it–was with me again.

It’s difficult to explain, because I bought this ring as a gimmick. It’s just what you do when you visit Ireland, but, the thing is: I didn’t just visit Ireland. I lived there and studied there. I laughed and cried there. I flirted with my first boy in a pub on Sea Road. I joined clubs and practiced Irish with old men at bars. I introduced my dance shoes to their homeland, and I saw the world from the top of a mountain (or what Austrians would call a “hill”). It’s just a plain silver thing, but, when I look at it, especially when I’m sad, I remember that I did all that, and I can do it again.

—

My Oberlin afghan(s). I’ve said it time and time again, so I won’t bore you with too much repetition: my time at Oberlin was weird. Completely enamored with the history of the place, I was also incredibly depressed and broken for most of my time there. One of my close high school friends died my freshman year, and I took to wandering alone in the early morning. I closed myself off from any potential friends in my new home, and my isolation deepened. I buried myself in my schoolwork to distract from a life that wasn’t at all what I had anticipated when I received my acceptance letter. I struggled with disordered eating, and I fell in love with the wrong person. I left a proud graduate and ran full steam into a heartbreak that would take years to heal.

But, here’s the thing. The whole time I was losing myself at Oberlin, I was also finding myself. I found a strength and a determination I didn’t know I had. I learned about social justice and humanism. I opened my mind to histories I never knew existed. I connected with the stars and the earth. I discovered new passions and tried new foods, and I eventually did make friends. Despite all the hardship, those are things I wouldn’t trade for the world.

I have two Oberlin afghans. One was given to me before I graduated. The Oberlin College seal (designed by a woman!) is emblazoned across the front in crimson and gold, and the motto, “Learning and Labor,” is embroidered in strong, bold letters. The other was a gift from the Oberlin Heritage Center when I completed my year of Americorps service there. It’s a simple white and red and depicts historic buildings and events in the town.

When I moved to Cleveland, one of the hardest changes was to no longer feel connected to the place where I lived. I had been in Oberlin so long–I had lived for its history so long–that I could barely cope with how displaced I felt in Cleveland. These afghans are my way of keeping that sense of place alive, that sense of belonging. Both represent a different experience I’ve had in Oberlin–as a student and a resident. Both remind me of the things I’ve overcome, of the lessons I’ve learned, and the people I’ve loved in a town I will never, ever forget.

—

I don’t own a lot of things, and I don’t want a lot of things, but I do love the things I have. If I did an inventory of my room right now–of every single mug, trinket, and article of clothing–every single thing would have a story. That’s just how I like it. I have individual socks that have a story just as long as the ones I sketched above. But I’m stopping here, because it’s late, and I want you all to still be my friends after you read this.

My life as a young person has been a transient one. My nests have been necessarily small. As the years go by, I will probably live in more cities than I ever dreamed as a child, and it might be years before one of those cities truly becomes home. I’m facing another birthday, another move, and grad school applications. With all the craziness, it’s easy to forget who I am and where I’ve been. Ownership is a bizarre concept, but I’m grateful the things I love are mine. They hold my memories (my entire life!) and keep my roots portable. Without them, I don’t know where I’d be.